STARBASE 1 ADVENTURES

Missions in the Starbase 1 LARP

A Comprehensive Guide

By Starport Industries

version 1.0 [2022 Edition]

Introduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A Note on Consent . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

S.E.A.M.S. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

Organized Chaos:. . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Improvisation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Planning your own Mission, Start to Finish. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The What . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . .

The When . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The How. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Logistics and Supply . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. ……….. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Networking . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . ………. . . . . . . . . . . .

Conflict Resolution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . ………... . . . . . . . . . . . . .

When to Say ‘No’ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . ……. . . . . . . . . .

Putting your Missions in Motion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Advertising . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Briefing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Timing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Execution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Debriefing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Challenging Themes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Deception . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Stealth Missions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Stealing & Relics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Prisoners & Hostages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Quick Reference Sheets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . .

. . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

When I first began really participating in Missions and Lorefare

at Events, it was only my third year at the Starbase 1 LARP (2022

for those counting). I recall picturing a chance to live out

scenes from Star Trek or a Firefly Franchise Game. A quiet “man

with no name” gun-for-hire type who shuffled into town and is

subsequently tasked by the denizens to do the jobs the denizens

haven’t the time (or lack of self-preservation) to do themselves.

I wanted to be immersed in this post-apocalyptic world, and I

didn’t know what awaited me or how I would begin. But I knew

despite my shyness, my eagerness could eclipse my anxiety.

I made my way up to the window at the WCC. I’d seen the “help

wanted” sign painted on a nearby board and inquired about ‘work’.

A husky man with a thick beard nodded warmly and told me that one

of the radios they operated was in need of replacement parts,

specifically vacuum tubes. The market for such tubes was thin,

rumour had it that the Crimson Caravan may have some in store. He

handed me a handful of burnt orange bottle caps and told me it

should be enough to purchase the part. I was to speak with him

when I returned with it.

With caps in hand, I set out to find the Crimson Caravan, invested

in seeing my quest through straight away. I had seen the camp sign

along Bartertown row, at the time on the South side of the City. I

strode up to the open back of the large dome and stopped at the

threshold. Within, a shorter fellow stood behind a barter table

while his armed Campmate sat across the dome and eyed me

surreptitiously. Acknowledging my presence, the shorter man

beckoned me in and asked if I’d come for trade. I nodded and

entered. He bade me browse the various wares on the table. I

scanned the collection and recognized no radio parts. So I asked:

do you have any vacuum tubes?

The short man smirked for a moment and asked me if I’d the caps to

pay. I held out the 10 or so I’d been given. He looked, and shook

his head. “It’s not enough,” he taunted. I, confused, glanced down

at the table and the caps in hand. Slowly it dawned on me,

realizing, in my naivety, I was being hustled for more caps.

My heart began to race. My left hand extended out the caps, my

right moved to my belt and un-snapped the holster of my pistol

audibly. I, uncharacteristically bold, asked again “Isn’t it?”.

The shorter Caravanner eyed my six gun, and shot a glance to his

compatriot across the way. They smiled and we exchanged the part

for the caps. I playfully backed, slowly, out of the dome, never

taking my eyes off the camp, or the grin off my face.

Eventually I made my way back to the WCC and handed over the

dingy, faded cardboard box that held the small glass vacuum tube.

Precious technology, lost in the pox-iclipse, in the long long

ago. The man behind the counter nodded, thanked me and handed me a

custom WCC bottlecap for my services. A trophy! A token reminder.

I was enthralled. I resolved later to participate in Missions as

often as I could, and to seek out such experiences wherever and

whenever they piqued my interest.

My ‘character’ and role may have evolved significantly these past

10 years and my shyness evaporated but never my passion for

immersive environments. It is because of this passion, and a

desire to create and share missions with others, that I wrote this

guide. So that each Member who endeavors to cross the threshold of

immersion, finds the Experience Gratifying, Amusing, Exhilarating

and Memorable, such as I have these past years. I hope it proves

useful, please enjoy.

See You At The Outpost!

Smitty

What follows is a set of Guidelines intended for the Creation and

Support of Missions at our Starbase 1 LARP Events. Participation

in a well executed Mission, can be an immersive, and entertaining

experience. People often participate because they wish to be

transported, even temporarily, into a futuristic World full of

Excitement, Intrigue and Danger. If you haven’t experienced this

kind of activity for yourself, it is critical to try out a few,

before trying to Run your own, as they will provide insight to the

kinds of Fun you can have. While most of the Audience and

Participants are aware that the perceived perils and challenges,

aren’t “Real”, efforts to shatter the illusion can likewise

shatter the enjoyment of the activity and potentially spoil the

efforts of hardworking individuals. Some of that is unavoidable.

However, in the spirit of the kind of oath Magicians might keep to

‘never reveal their Secrets’ sometimes you must conceal the

behind-the-scenes workings from your Audience to preserve the

purpose of the Game. Our Goal is to Create, Propel and Preserve

the Magic. Please consider some discretion when using this Guide

to plan Missions at the Event, and don’t Share what you’ve Learned

& Planned irresponsibly, to preserve the Surprises and

Immersion for as many People as possible.

AN IMPORTANT NOTE ON CONSENT

Participation in a Mission is a form of Social

Contract. The Parties involved suspend their disbelief to a

degree, and pretend to be characters living in a futuristic World.

However, the Events are not “Real”, and real Threats to

Participants Survival, or Safety should never happen.

Not everyone wants to Play the same kinds of Games, or indeed Play

the same Missions in the same way. Everyone has their own ‘House

Rules’.

It’s ok (and encouraged) to make Disclaimers on Missions that

feature more Challenging, or menacing aspects. Ask your

Participants what kind of Mission they are looking for, and allow

them to set their own comfort to playing along. Goals where

Participants might complete it by Intimidating, Threatening, or

Coercing Parties In-Character, should always be Performed in the

Open, in Public Spaces wherever possible, Theatrically,

respectfully and in the spirit of Good Sportsmanship. It should

always be apparent that a Game is taking place, and not a real

Health, or Safety Concern.

Consensual Disorder/Unrest is Acceptable so long as it is done

Theatrically; acting deliberately, or somewhat exaggeratedly

Dramatic for the Performance. And often, with a Smile. Such that

any Mission activity could not be mistaken for Real Danger, or

imminent Violence, by a casual Observer. Non-Participants should

not have reason to believe anyone is really in Trouble, or that

they aren’t Safe. Additionally, things like brandished Prop

weapons should be kept at safe distances from other participants

unless the involved parties have agreed to (or better yet

scripted) something otherwise. If the people who chose to be

involved or the surrounding audience aren’t having fun, or don’t

understand that it’s just for show, you’re probably doing

something wrong.

All Gameplay should follow S.E.A.M.S. guidelines (Detailed below).

Participants should be actively and enthusiastically consenting to

participation in Gameplay. It is always appropriate to ‘break

character’ or pause an activity to check if participants are in

good order or to address questions or concerns.

Players should never conduct themselves or the Mission in a manner

that makes any other participant, non-participant, event personnel

or others have serious cause for concern. Harassment of any kind,

violation of Codes of Conduct, or breaking of county, state, and

federal law will not be tolerated.

WHAT MAKES A

GOOD MISSION?

To make things simple when designing, and

running your Missions you need to ask yourself: Where are the

S.E.A.M.S?

Safe, Enjoyable, Accessible, Memorable, Sustainable. We’ll go over

in detail what each of these mean:

S - Safety: Always follow State and Federal law and Event Rules

and Guidelines. Is your mission safe to participate in? You may

think this would be obvious, that even the most idiot-proof idea

would be safe. But idiot-proofing is a perpetual task, so often

the best you can do is make something idiot-resistant. Does

participating in your mission involve any kind of elevated risk?

Does any part of the mission make things difficult for Security or

Medical personnel? Are participants likely to encounter situations

which may lead to real-life threats or pose health hazards? Does

your Missions instructions or goals have room for unsafe or

problematic interpretation? Are participants likely to put

themselves or others in harm's way in the pursuit of completing

the mission? Are unknowing/unwilling audiences going to be caused

undue concern or hazard?

E - Enjoyable: Is your mission any fun? Would YOU want to

participate in it? Is your mission a

foot-slogging/exposition-dumping chore? An annoying series of

A-to-B? Is it a lot of “hurry-up-and-wait”? Participants standing

about, with no clear timetable or secondary goals. Is it

confusing? Two Team leaders in quiet conversation while a room of

willing participants mill about with their hands in their pockets.

Unable to hear or see the goings-on, distant and disconnected.

Would it be fun for a first timer? What about someone who’s done

many missions? Is it only fun with one participant? With many?

Consider how fun the Mission might be with a variety of

participants in a variety of groups and configurations. Is it fun

even if they don’t finish or if they fail? What are the stakes?

Are there consequences to the Mission not going according to plan?

Can it still be fun if the goals change on-the-fly to meet

unexpected challenges of the wastes?

A - Accessible: Are your missions possible to do by everyone? Are

the goals clear and understandable? Can you do it if you’ve never

played before? If you know nothing about the lore or history of

the event? As a Mission creator or runner your job is to convey

not only how people can participate but why they should care about

the goals. Can participants of all ages, sizes, shapes and

abilities take part? If your mission requires or would benefit

from any special knowledge, resources or abilities you need to

establish that in your briefing. Consider how your mission will be

interpreted by the audience, try to word it as clearly as

possible. It should be easy to learn but difficult to master. If

you can’t make it accessible to everyone then be specific when

advertising or recruiting for it. Like a job offer, let your

participants know upfront and early what is expected of them and

let them be the judge of their own abilities. This also goes for

those witnessing your Mission in action. Can they understand

what’s happening? Can they, to a degree, be ‘in’ on it too? Make

your audience a part of what we call “Inclusive Exclusivity” by

maintaining the illusion that they are “in” on the ‘exclusive’

action that is technically accessible to everyone.

M - Memorable: Do your participants have the chance to feel

immersed? Do participants get to be part of some conflict

resolution or bigger-picture plot? Does the mission fit into you

or your group's lore? Do they solve a problem or perform a task

that you couldn’t somehow do yourself? Does your mission encourage

or discourage audience participation? Does the experience hold up

as its own reward? Do your participants leave with any reward? The

Satisfaction of a job well done? The thanks of the weary

Teamsfolk? A position among the ranks of your trusted masses? Team

caps? Play-currencies? Unique Loot? What do they take away with

them after they complete (or fail) the mission? Not every mission

needs some kind of payment, but some participants will be

motivated by the idea of ‘earning’ play money by participating.

S - Sustainable: Do you only run the Mission one time or many

times? Can it be run only a few hours or through the whole of the

event? Do you have backup plans for unexpected or necessary

changes? Running a Mission means advertising its availability,

having someone available to give the briefing, supplying that

mission (if props or play-currencies are changing hands), having

someone to give the debriefing and attending to questions and

changes that occur. It can be done with as few as one or as many

as you have in your group IF everyone is up to speed with what to

do. Does your Mission require so much explaining that it’s tough

to get participants caught up? Does it require you to spend all

your time in camp? Does it cost you lots of money or energy or

time to run it? Design with you and your group's needs in mind.

Burnout is real and can be very damaging to the otherwise fun and

rewarding experience of running missions.

ORGANIZED

CHAOS: WHEN THINGS GO WRONG

“SHIT Happens”

When the Event as a whole is a Festival, then Missions are like

Festival Games. Always expect a percentage of unpredictable

change, and try not to let it disrupt your Fun too much. You might

get many interested Participants, you may get none. You might run

out of Supplies on the first day, or go Home with extras. You

might, for example, organize everything to happen on Wednesday at

noon. But then you discover that the Opening Ceremonies have been

pushed back an hour, and now are taking place at the same time.

Your best Street-Barker/Advertiser may have Car trouble, and can’t

make it till Thursday. The ‘W’ (wind) might kick up, and force

everyone to take cover for hours. The Team who was supposed to be

at the Meeting, got surprised and raided by an Enemy, and couldn’t

show. The saying “Shit Happens” applies here. Plan Missions that

are adjustable, and plan with the mindset that nothing that goes

unused, is wasted. Any Missions, or machinations you didn’t get a

chance to use where and when you’d planned are good candidates for

use elsewhere. With clever planning, any Mission you didn’t use

one day can be folded into the next.

Example: Your Mission is to deliver an item from your Camp, to a

distant ally. You discover that due to emergencies the ally camp

is now unable to Staff their Camp to receive the item.

Could, instead of abandoning the whole Mission, you find another

Team who can accept it? Or perhaps some manner of passive

drop-off, wherein the Participants deposit the item in the Ally

Camp's improvised Mailbox? Perhaps you send the Participants off

to deliver the item in a timeframe knowing the Camp will be empty,

and when they return with it undelivered, you thank them for

bringing back the valuable information that the Camp is empty, and

spin a Story that perhaps some larger treachery is afoot. Perhaps

you escort the Item yourself, with Participants in tow, and

announce the Mission a success upon arrival. Adapting a Mission to

changing circumstances will be invaluable. Planning ahead and

keeping backups in mind, will preserve immersion.

"YES... AND"

When you begin to run more complex Missions that intersect with

other Groups and Teams, and their own complex Backstories and

Motives, you will encounter what, at first, may appear to be

Obstacles, but are Opportunities in disguise. Often there may be

situations that arise from individuals Actions, clever

Workarounds, or Shenanigans that directly conflict with your

Plans. Instead of allowing the events to spoil your Work, “Yes,

And” them. As a Rule of improvisation: rather than denying the

actions as canon, accept what another participant has stated or

done ("yes") and then expand on that line of thinking ("and") as

often as possible. We often joke that a planned mission, prior to

the event might be 70% scripted and 30% improv, but a mission

during the event becomes 70% improvised and 30% scripted. It’s ok

to have to ‘embellish the story’ or contrive new plot points from

time to time to make things work.

Example: Perhaps a ‘rival’ group has decided to also deliver the

same kind of item to your ally.

Instead of trying to get the rival group to stop, perhaps work out

an arrangement with the other group behind the scenes so that

participants in your delivery mission can now confront “rival”

group participants for their item in a rock-paper-scissors battle

and seek out the reward for delivering both to the ally Team.

Perhaps you can arrange a meeting at another group or venue as

middlemen and have both opposing Teams meet to work out this

territory dispute in-character. What was an obstacle can now be

made into a fun lorefare opportunity for multiple parties.

Sometimes participants or other groups will do something that is

totally unexpected, which, intentionally or not, totally subverts

your mission plan. For Example: a ‘rival’ group has swarmed your

camp with dozens of mercenaries and they ‘demand’ you hand over

all of your delivery items. You could break character, tell them

‘No’ and probably send them away empty-handed and with an

anticlimactic end. But with “Yes...And” you could instead hand

over the delivery items vowing theatrically to gather fores to

raid their camp in return, or perhaps tell them they are too late

and that all the items have been delivered but you’ll exchange

some other artifact or some valued information on where they can

find more, effectively re-directing them to a sidequest. Events

that might otherwise terminate the plot can instead be plot

twists.

Other Examples of when Yes...And applies:

Your Team sets out seeking information on the whereabouts of a

fabled vault, but only a handful of people know about it’s

location. You find one of them but this person has already given

away the clue-prop to another vault seeker. Instead of ending the

mission right then you and the participants visit other camps and

spread the word that you’re putting a bounty out on anyone

carrying a clue-prop to the vault.

Example: a group of waste-pilgrims have mistaken your mission

[THINGY] for one belonging to another group. They retrieve the

[THINGY] and deliver it to Camp B. Instead of reprimanding the

pilgrims and just retrieving your item you can shift and open

trade with Camp B for return of the [THINGY] or (with a bit of

planning and improv) you can visit Camp B for a “Raid” to get the

item back with a high-stakes game of cards or Rock-Paper-Scissors.

PLANNING YOUR

OWN MISSION, START TO FINISH

Some Teams have an individual Member act as the go-to for

organizing, and tracking Missions at the Event, to help keep

everyone (relatively) on Schedule, but such a position may not be

necessary if you’re just starting out. Whatever your role, it’ll

help to write down the important following information when

designing a Mission. What, When & How.

PART 1: THE WHAT

What's your Agenda? Think about what you are trying to accomplish

with the Mission. Is the goal to:

● Encourage Participants to Explore the Event, or some aspect?

● To Network with other Players, or shared interest Groups?

● To Promote an individual's Cause, or Camps Notoriety?

● To raise awareness for an Event or Activity you Host?

● To convey a Theme or advance a Plot arc?

Or perhaps some combination of any of these. It’s ok if your

objective is nebulous, but communicate that to your participants.

PART 2: THE WHEN

Consider your Timetable to Plan your Mission, if possible you

should start some Weeks before the Event, to give yourself, and

any Groups or Teams you may Partner with, time to work out

Details, and prepare. The longer you have, the better prepared

you’ll be for when “Starbase 1 Happens”. Some of the more complex

Plots begin Planning, and Promoting months in advance, especially

if they involve many Groups, Teams or Event-wide Participation.

Missions can be totally improvised, and still fulfill S.E.A.M.S,

and not every Mission will require planning ahead of time. It's

highly recommended that you perform a Review of the Plan, with any

participating Groups or Teams, before it takes place at the Event.

Have a good idea of the where and when of the mission, how long

the mission should take to complete (people will ask) and what to

do if the plan has to change. Before finalizing your timetable,

have some idea of what other shows or activities may be taking

place during that time or day of the Festival.

Your Mission can be a simple 5 minute Task, or a sprawling

multi-day Trek. In our experience, starting off with a short

straightforward Goal is best. A complex, multi-part Story is easy

to lose track of, or to be abandoned. A simple fetch Quest can

easily transform into an Event spanning, convoluted Contest when

Events intersect. It’s ok to start small and build over time.

PART 3: THE HOW

Logistics and Supply

For every step you add to a Mission the potential for

misinterpretation, unexpected changes/consequences grows

exponentially. Make time to meet with and review the plan or

distribute any props or notes with any contributor parties at the

event. Ask them about changes to the plan or schedule (This step

could be performed as its own courier mission). If you’re using

props consider the Navy Seal idiom that “Two is One, One is None”.

Having only one of a particular prop means if that prop is

damaged, destroyed or lost your plans may collapse. It’s better,

whenever possible, to have 2 or more of any prop, or a

substitute. Props or symbols, with unique, distinguishing

marks or names on them are better, so they can’t be confused with

other props or decorations in other camps.

Example: Your mission is for participants to go and

collect a “gold” bullet casing from another camp. But bullet

casings are common as part of outfits or decoration and

brassy-gold in color, how are participants supposed to know which

one they are supposed to collect? Could they get confused and

visit the wrong location? Could they ‘cheat’ the mission

(intentionally or accidentally) by turning in just any bullet?

Networking: Involving other Teams and Groups

Pooling resources or labor with other individuals or Teams is a

great way to promote and expand your Missions reach. Temporary

alliances and ‘truces’ between groups help foster awareness of

your Mission as well as theirs and can lead to unexpected (and

often hilarious) results. Don’t be afraid of reaching out to other

established Lorefare/themed groups to find out what events and

activities they may have going on that you can tie into. Start a

group chat and communicate your plans with them and their members

before an Event to cut-down on the ‘telephone game’ of

misinformation. If you have to change or improvise plans during an

event, communicate the new changes as clearly and plainly as

possible (in writing preferably) to all the parties involved.

Involving other groups also means you’ll probably intersect with

whatever their other plans or missions are, sometimes these can

disrupt or derail your plans. Diplomacy, and “Yes...And” are

indispensable here. Groups are sometimes working at

cross-purposes, often there are moments of semi-organized chaos,

and breaking character or conferring with other organizers may be

necessary. Don’t get too bogged down in the details, you can

always contrive a lore explanation when the immediacy of the

moment has passed. Preserving the momentum and spirit of an

activity is more important to your participants and audience than

getting every loose-end tied up neatly.

Conflict Resolution: “Armed” vs. “Unarmed” Missions

In a desolate wasteland all manner of protagonists, factions and

antagonists thrive. Often armed war-parties will clash with one

another, and your participants can find themselves at the wrong

end of a (prop) weapon. This can be thrilling, or tedious

depending on how it’s performed and especially how it’s resolved.

Unless everyone intends to shout “pew pew pew” at each other and

fall down (which can be comical, if not very immersive) you’ll

need a satisfying resolution. That can be achieved in essentially

2 or more ways.

If your Mission is “Armed” (assumption of Conflict with Prop

Weaponry) then some instruction for Conflict Resolution should be

provided in the briefing. For practical purposes, a Challenge Game

of Rock-Paper-Scissors suffices as a Gun Fight Stand-in, as it’s

familiar to many, and can be performed with no Equipment. However

many alternatives exist. Games like: Odds and Evens, Thumb

Wrestling, & Footraces likewise can be performed anywhere.

More traditional games like: Tic-Tac-Toe, War, Dice or Card Games

can be played in short order with very little or no equipment.

Even if your Mission is “Unarmed”, and suppose Participants are

only supposed to retrieve something, or acquire information, there

is a good chance some manner of conflict could arise. Provide your

Participants with some guidance as to what options they have, like

Negotiating, Bartering or Charming their way out, or Collaborating

with other Teams/Groups/Participants.

Example: Team A is hiring participants to get Team B to stop

sending raiding parties after them. Team B could be swayed by a

show of force (“Armed”) mission or convinced to target another

Team with better prospects for the raids (“Unarmed”). Team A

coordinates with Team B beforehand to allow for either option to

successfully complete the mission. Team B will ‘back off’ if

participants show up with a few well armed mercenaries OR if they

send a negotiator to ‘convince’ them to switch targets.

Look for opportunities to create artificial tension, rather than

direct Conflict, and allow your Participants Options in resolving

the Tension, before it “boils over”. Not every fetch-quest needs

to end in a shootout. Many participants won’t be able to muster an

armed group large enough to match some Teams. Some participants

won’t have any skill at public speaking or being charismatic

enough to sway a group. Sometimes circumstances align to make for

better stories than what was ‘scripted’ to happen. Don’t overlook

eager participants' capacity for creative problem solving.

Sometimes giving them the option to come up with the solution is

more fun. This usually results in a great opportunity for

“Yes...And” when adapting to the aftermath.

KNOWING WHEN TO SAY NO: DECLINING PARTICIPATION

It’s not always easy to turn down people or to exclude someone

from an activity especially in a festival atmosphere but as a

Mission giver you have a social obligation to ensure that the

S.E.A.M.S. are showing. Sometimes you’ll get potential

participants who want to engage in missions but repeatedly

demonstrate an inability to cooperate, be safe, or adhere to the

guidelines. Some may want to unsafely ignore or change important

plot points in favor of one of their goals. Some may be too under

the influence to pay attention, or some who simply don’t

understand it’s a game. Don’t be afraid to withdraw your

invitations or decline to interact with them.

The enjoyment and well-being of participants at the event takes

precedence and you are not obligated to manage others who can’t or

won’t respectfully cooperate.

This is especially important when it comes to participants who

demonstrate a disregard for consent or are a bit too enthusiastic

about the more menacing aspects of some missions. Use your best

judgement when selecting participants but if you have to remind or

correct someone about safety, consent, or guidelines more than

once, chances are they will do something unsafe or unfair again

and you’re better off sending them away or ending the mission.

Example: Team A is “looking for an important relic”, but Team D

keeps showing up and lying to everyone that the item of junk they

possess is Team A’s important relic. Team A could choose to

decline the interaction and politely correct them or just not

accept Team D’s ‘relics’ as valid. Team A isn’t obligated to

“Yes...and” someone else aiming to spoil their fun.

Example: Team A is offering to pay people to escort them across

the Outpost, but Mercenaries from Team C show up, and are so tipsy

they can’t walk straight. Team A should politely discharge them

and look for other Participants.

PUTTING YOUR MISSION IN MOTION

So you’ve got the What, When and How figured out and you’re ready

to start running it at an event. But where to begin?

Advertisement (Before, During and After)

How do people find out about your Mission? Social media posts,

images, and videos before the event are a great way to advertise,

there are Mission and Team Lore relevant groups and often a list

of the accumulated participant-driven activities at that year's

event available online. You don’t have to be a skilled social

media manager to create a straightforward post about your Missions

Context and Lore. A blurb about what’s going on and an image which

includes the important stuff (like where to start the Mission, and

when) is sufficient. Promotional Posts on Social Media Groups

(like Starbase 1's BBS) should be limited typically to at most

once every two weeks leading up to the event.

If your intention is to exhibit a plot that unfolds and adds

context to your mission then include hashtags and a link to where

your audience can find the rest of the posts they may have missed.

Lowering the barrier for newcomers to find and understand the

‘story so far’ will open the door to more audience engagement.

Getting the word out can also be fulfilled at an Event with

community bulletin boards or by arranging to have some part of it

hosted at one of the many Team-venues. Barkers or street

advertisements outside your camp or on populated corners can also

draw in participants. Ensure the starting location and time of

your mission are prominent. Starting in 2022, Teams began the use

of the triangular ‘!’ sign (pictured left) on their Camp

Decor, or Costume to indicate that Missions are available at that

Camp, or with that Individual. Displaying it prominently will help

Guide attentive Participants towards your Mission.

Document your Work! When possible take Photographs of the Mission

in progress, or keep track of the number of your Participants, and

the feedback Reports or Results. Not only will you be able to use

this data to grow and improve your Missions, but you’ll also have

a Fun record of your Team's Contribution to the Event. You can use

the Data and Photos in Promotional Material for future events.

Consider posting an ‘after-action’ report Post Event, to summarize

your Mission's outcome, and any memorable Moments, or

Contributors.

BRIEFINGS

Unless your Mission is literally as simple as a single sentence of

Instruction, you’ll probably want to give out more Information.

When potential Participants arrive where the Mission is taking

place, having someone available to greet them, and give a short

Briefing, or Documentation on display, for more information is

key. Having good diction, is also critical. Unclear, or vague

Instructions have, in the past, led to some Fun and Hilarious

results, but have also led to misconstrued Actions, and

embarrassing or troubling problems for Event goers.

In the briefing you’ll want to shortly reiterate:

● Who You, or your Team is

○ Example: “Welcome to [CAMP A], are you here about [MISSION]?”

● Your in-Character Motives for running the Mission

○ Example: “We need Couriers to Transport [THINGY], safely across

the Outpost, our Team wants to use the [THINGY] in a trade deal

with an ally”

● The specifics Goals of the Participants

○ Example: “Find a [SPECIALLY MARKED THINGY], and return it to

[CAMP A], you might find the [SPECIALLY MARKED THINGY] being kept

by [CAMP B] ask them about it”.

● What they can do if they need additional information later, or

have Questions/Issues, that arise from the unexpected

○ Example: “If you can’t get it from [CAMP B], or if they aren’t

around for a long while, we may have another option [Tie-In to

another Mission, or Backup Plan], return here, and let us know.”

○ (Optional)Example: “You might be able to find [SPECIALLY MARKED

THINGY], at these Camps [Pointing to Event Map on display]

● Potential reward for completion of the mission

○ Example: “If you bring it back we may have more rewarding work

for you in the future”

○ Example: “If you bring it back you’ll have our deep gratitude”

○ Example: “If you’re successful there's a few caps in it for you”

● Reiterate the Goal and ask if they’ll accept the mission and if

they have questions now

○ Example: “Any questions? Find us that [SPECIALLY MARKED THINGY],

and good luck!”

In Theater, Playwrights use an “aside” as a technique for a

Character to speak lines that the Audience can hear, but the other

Characters on Stage are not aware of. Use something like this

anytime you have to temporarily break character, make safety

reminders, exposit on confusing details or explain in simple

“plain English” terms, what to do.

TIMING

Sometimes you’ll plan a mission that requires participants to

attend something at a later place and time or to wait for you or

one of the various denizens to arrive or a deal to go down. Convey

an estimate of the kind of time commitment your participants can

expect. Not all participants can or want to commit hours and hours

to a mission. You can still offer a complex series of tasks and an

epic plot spanning the whole event but your attendance and

continuity may suffer.

For activities that take more than 5 minutes say they take 15. It

takes time to walk or even drive to and from camps at events. For

every additional camp or location they must visit add 15 minutes

or so to the estimated time. If they have to wait for someone to

return to their camp you may want to add another 5-15 minutes

depending on how likely the target is to be in camp and brief your

participants on what to do if the target doesn’t show in a

reasonable amount of time.

Be prepared for delays, rescheduling, or changes. That’s part of

the experience. Sometimes a participant will solve your complex

multi-step riddle puzzle in seconds, and sometimes they won’t be

able to find their way out of a cardboard box with 2 hands and a

flashlight. Have backup ideas and be ready to “Yes...And”.

EXECUTION

When addressing Teams or Groups of more than 4 or 5 Participants,

Project. Your. Voice. That doesn't mean you have to shout

everything, but be considerate of your Posture, Physical Facing

and Pronunciation. Participants who can’t hear or understand

what’s going on, will quickly lose interest (and may wander off).

We have seen numerous grand Schemes, or Confrontations fall apart

because no one understood what was going on or what to do.

Keep your Speeches and Stories relatively short and to the point.

Audiences greater than 10 people typically will pay attention for

about 3-5 minutes without engagement. Keep your audience engaged

with the plot as it unfolds. Audience participation is good.

There will always be participants who accept a mission and quit it

halfway through or get frustrated or disinterested/distracted and

abandon it. By communicating what to expect you can lessen how

often this happens and save potential wasted time, effort and

resources for everyone.

If your Mission has a failure-state (a way to ‘lose’ at it) hint

at it or make it explicit in your briefing. Not every Mission

needs to be easy, but they should be challenging, yet achievable.

Partial success should be recognized, and having more than one way

to complete the Objectives is best.

Learn to lose gracefully; Winning every Conflict, and coming out

unscathed makes for very boring, or Non-Existent Stakes.

DEBRIEFING

When participants are done with the Mission how do they know?

Rewarding them upfront works for simpler missions, Returning to

the Mission-giver or having some way to verify their participation

works for more complex goals. Offering a debriefing will recap how

their in-character actions aided in your group's goals and provide

the players a sense of accomplishment. It’s also a great chance to

tie-into other plot arcs, missions or events. An example debrief:

● Any Kudos due the participants

○ Example: “You did well finding [THINGY]”.

○ Example: “Ah, you found 3 of out the 5 [THINGY] we were looking

for” ● Your in-character strategy now that the mission is over.

(Tie-ins for other Missions you may want to offer them).

○ Example: “Now that couriers have been transporting [THINGY]

safely across the wastes, our trade deal with [CAMP C] can go

through later today”

● What the consequences are if they fail. (Tie-ins for other

Missions you may want to offer them).

○ Example: “Without [THINGY] we’ll have to give up more goods in

our trade deal with [CAMP C], maybe they’ll reconsider if we. . .”

● (Potential) reward for completion of the mission (if applicable)

○ Example: “Give this note to the door-person at [CAMP D] for

entry to their VIP lounge”

○ Example: “pick something out from this box of barter goods”

○ Example: “Here's a Team Cap as a token of goodwill”

○ Example: “Here are the [play currency] I promised you”

CHALLENGING THEMES

Themes involving the ‘darker’ aspects of life on an Outpost are

difficult, and can downright be triggering for some. They can add

Gravity, Tension, and Stakes to a situation but, if done

improperly can result in a lot of trouble. We encourage Creators

to lean more towards the Festive atmosphere of the Event and

choose more Mischief than Menace. It’s important to make

Disclaimers about the Content of the Mission prior to sending

Participants into the fray. Even so, there are some Topics or

Themes that have never, and will never be appropriate to Roleplay

at Events (See Starbase 1's Code of Conduct). The following is a

list of Topics that have can be Run at Events, and still adhere to

S.E.A.M.S Guidelines.

Deception

Sometimes you’ll need your Participants to Lie to Distract,

Mislead or lure a Target (or Targets) to accomplish something.

This can be Fun, and produce some excellent Ambushes, Comedic

Mistakes, and Pretend Treachery. But there are some things that

are off-limits to lie or be deceptive about.

Examples:

● Faking Real-Life Medical or Security Emergencies: Don’t Joke

about how ‘Grandma is in the Hospital’ or ‘Your tent is on fire’

these can really endanger people.

● Misrepresenting a Member of Staff or Personnel: Don’t Joke

about, Impersonate, or include Staff, Event Security or Law

Enforcement, as part of your Mission.

Contact the GM's for any Teams/Groups you want to ‘deceive’

beforehand, and elaborate on your Plan. That way you can still run

the Missions with those Teams/Groups, but participants (who aren’t

“in '' on it) will understand the deception as Lorefare after the

activity.

If you’re unsure if something is ok, check it against the

S.E.A.M.S. and if you’re still not sure, err on the side of

caution and don’t do it.

Stealth Missions

Stealth is a valid alternative to direct confrontation for less

combative or more covert types of participants. Consider having

participants perform reconnaissance, courier goods behind

perceived enemy lines or extract valuable assets from guarded

locations. Stealth should be handled with a similar mindset that

combat missions follow. If the participant is caught sneaking

around, there should be a challenge game or some kind of

failure-state. For Example:

● Participants must observe and report on the comings and goings

of an enemy camp for a critical few minutes

○ If participants are caught or observed spying, then “the enemy

knows we're onto them” and will alter their plans. The

intelligence is ‘useless’, the mission failed.

19

● Participants must smuggle a crate/box/prop full of [THINGY] past

an enemy patrol or camp.

○ If participants are caught they should play rock-paper-scissors

for possession of the [THINGY]. If they win they make their escape

with the prop, if they lose they hand the prop over to the enemy

and report back that it’s been taken.

● Participants must sneak or go undercover into an enemy camp

(being respectful of camp boundaries, hours of operation and

marked entrances and exits) and “steal” a relic or [THINGY] from

its displayed position.

○ If they are caught in the attempt the mission fails and they may

not try again today.

○ If they are caught fleeing with the item they can be confronted

and a tense game of Rock-Paper-Scissors/challenge game ensues for

possession of the item.

This last example can be the most challenging and the highest

stakes but also has the most potential for being misinterpreted.

(See below)

"STEALING" THINGS, AND RELICS

Firstly, there are always people who need this repeated often and

loudly: DO NOT JUST STEAL THINGS FROM PEOPLE'S CAMPS. THAT IS A

VIOLATION OF EVENT RULES AND STATE LAW.

The number of Teams that will create unique

items of Cultural significance to their Team or Group the

Community referred to as “Relics''. The various factions got into

a habit of fighting over possession of the relics as one side or

the other would take or capture the item only to ransom it back.

Eventually, rules were established to ensure the safe, enjoyable

and respectful participation of the other Teams in attempting to

essentially play ‘Capture the Flag’ with the Relics. The Items

would be marked with a distinct Exclamation Symbol. This Symbol

meant the Item could be intentionally ‘Stolen’ from a

Participating Camp. The Thieves however have to leave a Calling

Card in the item's place, or via Courier; a Note establishing what

was taken, who took it, and some indication where to go to find

it. Without the Calling Cards, Relics would go missing, and

chaotic searches, and accusations would be commonplace. Also

without them, the Relics wouldn’t be able to be found and returned

until the next year. The practice of marking items with the “Steal

This Thing” Symbol continues today, though the items needn’t be

Cultural Icons.

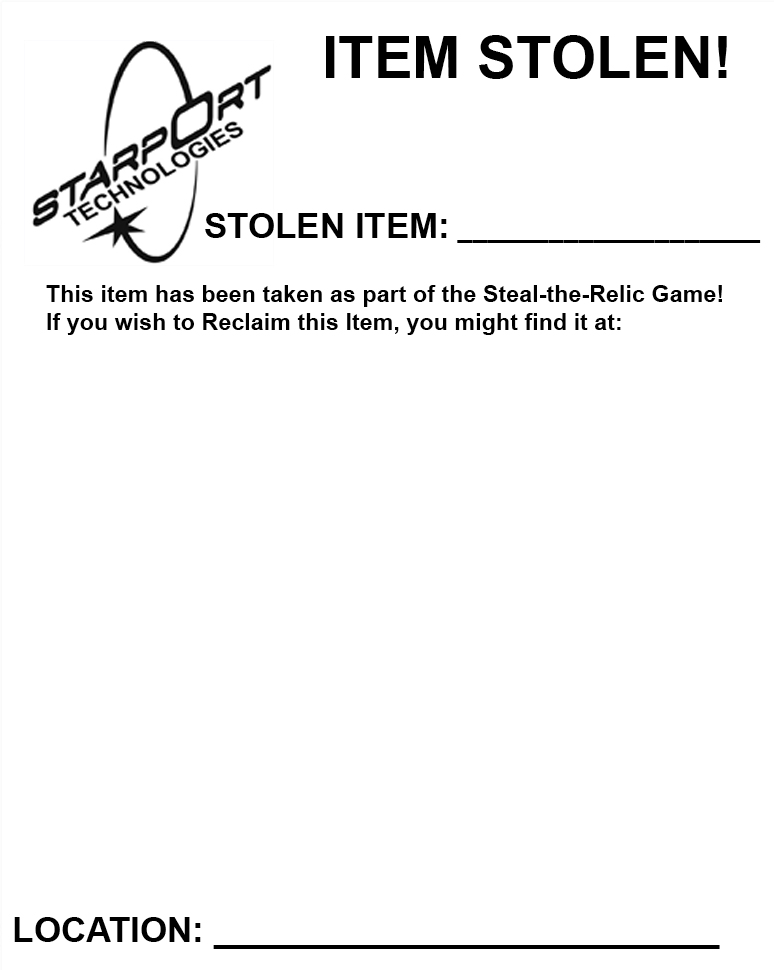

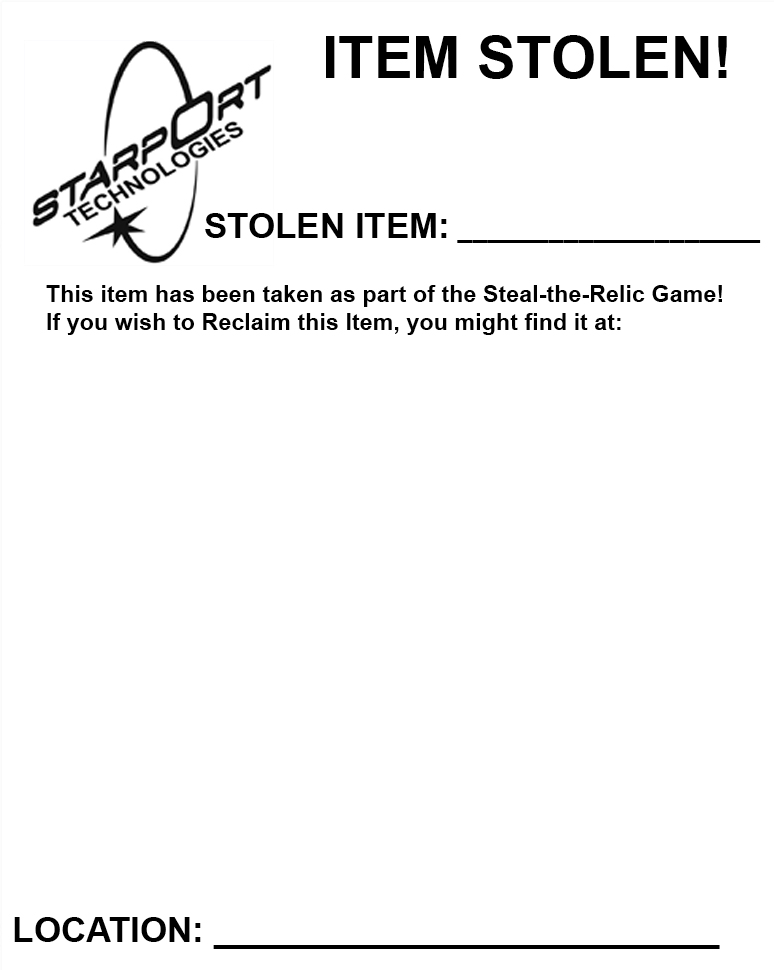

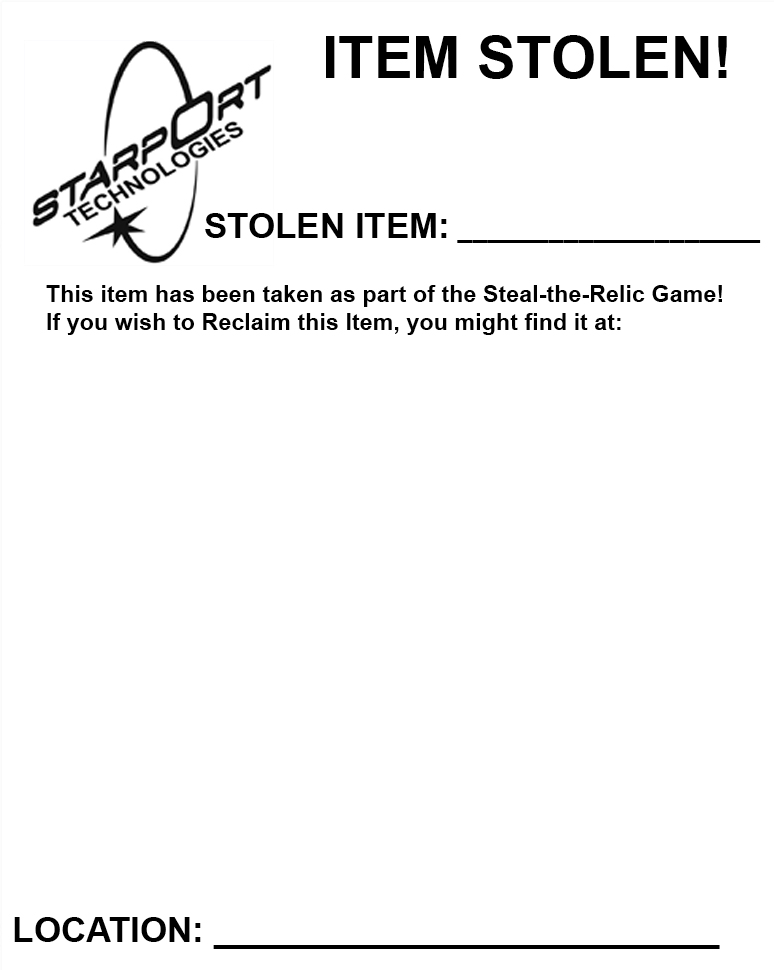

Its counterpart; the calling card (or note) should contain What

was stolen, Who stole it and Where (or what camp) it can be found

in. The notes should be left in the place of the item or delivered

promptly via courier. Pictured right is an example calling card

The Starbase 1 Pirates leave pinned in place of the item. There is

more space on the back of the Card for elaborating or leaving

additional notes. The front prominently features the Team logo and

name, what was stolen and where (usually on the map or cross

street) the Outpost Camp is physically. That way the Victims have

some indication of the chain of events, and don’t have to chase

dead ends if they want to reclaim their Property for Non-Game

related reasons. If you’re keeping the item mobile, or on your

person, consider Writing some of where you can be commonly found.

If Couriers are leaving the Card, explain what it is, and fill it

out for them. Instruct them on who and how to deliver it.

If you’ve stolen something and left (or delivered) a calling card

then consider prominently displaying the stolen item in a public

or semi-public trophy space in your camp, unless for scripted

reasons you’ve hidden it. If you trade/sell/exchange or lose the

item to another Team; get a calling card from them and keep track

of where the item changed hands. You wouldn't want your cool prop

to get really lost or stolen so be considerate and use your best

judgement. Finally: DO NOT JUST STEAL THINGS FROM PEOPLE'S CAMPS.

THAT IS A VIOLATION OF EVENT

RULES AND STATE LAW.

PRISONERS AND HOSTAGES

Missions that involve taking ‘prisoners’ or ‘hostages’ should be

used sparingly because they require participants to exercise more

caution and consent than those involving inanimate objects.

Consider using personal tokens to represent “captured” groups.

Example: Team A and B face off as part of a conflict. They

rock-paper-scissors challenge and Team A loses. Team A gives Team

B a symbolic token representing that Team A now has to refrain

from participating in the larger conflict until their allies can

win against Team B and set them “free”.

In the past “Prisoners” or “Captives” who were captured only role

played remaining captive until they could be swiftly returned to

the captors camp or a ‘safe’ location. Once there the captives

could return to normal activities and go about their day,

returning later to continue their role as prisoners when it came

time to ‘free’ them or pay the ransom.

Example: Team A has “Captured” Team B’s Leader in a daring raid.

Team B’s leader is paraded back to Team A’s camp. Team B’s leader

is then released to go about their day's activities or invited to

lounge as a guest at Team A’s camp. In the Lore their “character”

still imprisoned in Team A’s Camp and Team B must try to free

them, but the participant should never physically be required to

stay for the length of their ‘imprisonment’ (some enthusiastic

participants may wish to stay, you can always ask). Later in the

event Team B’s Leader returns to Team A’s camp and returns to the

role of captive, just in time for Team B to show up with the goods

to pay the ransom or enough guns to free their leader.

If, for plot purposes you absolutely must use live participants as

prisoners coordinate with the intended prisoner beforehand. Talk

to them about your plan and figure out what schedule works best

for them to be ‘captive’ during the plot. If you're capturing the

participants at the event, you may want to coordinate a general

place and time frame. Any participants in this kind of mission

should feel free to role play but must conduct themselves in a

manner that makes it apparent that everyone involved is consenting

to participation, especially the captives. Do not under any

circumstance, attempt to touch, move or restrain attendees without

their express permission.

The ‘Restraint and Capture Protocols’ detailed below should make

clear the rules for doing so while allowing captives a chance to

roleplay escape or resistance and still following S.E.A.M.S.

guidelines

RESTRAINT AND CAPTURE PROTOCOLS

● Any Restraints must NEVER be tied or closed in such a fashion as

to cause the wearer pain, undue stress, or make it unsafe for them

to move in an emergency. Simply wrapping or looping things like

Rope or Chain once or twice, is sufficient.

● The Person being restrained, retains Control of their Restraints

at all times, they may drop them/shake loose of them at any time

to prevent snags, or being dragged anywhere. Do not secure the

restraints to the Participant. Do not Pull or Tug on anyone's

Restraints without Consent.

● Individuals are considered Captured when they have lost a

challenge game and chose to be restrained. Captured persons may

remain Captured as long as there is at least (1) Guard within arms

reach of the Captive or if there is at least (1) Guard within arms

reach of the restraints after they have been restrained. However

Captured individuals retain control of their participation in any

further Gameplay and may cease being restrained or moved at any

time. You don’t actually haul people away against their will! They

play along for the fun of it, but can pause, stop or leave

anytime.

● As part of Gameplay Captured individuals may Free Themselves

when No Guard is present or within arms reach, or they are “tied”

to something they can move themselves. Escaping prisoners should

count to (90) seconds and pantomime unlocking/undoing the

restraints. Example: “Tying” a prisoner to a loose tire means they

can roll the tire away to attempt escape. Tying them to a

structure means they can only work to free themselves when no

guards are watching. Prisoners thwarted trying to escape must

cease attempting the escape when the restraints are tagged by a

guard. A valid tag is any light touch on the restraints. Prisoners

may re-attempt to escape after a tag and a grace period of at

least (10) seconds, but must begin the (90) second count again

from.

● Breaking a Prisoner Loose is possible whenever there are no

guards present. The Jailbreaker should count to (30) seconds and

pantomime unlocking/undoing the restraints. If a guard is present

and catches someone attempting to free the prisoner they may also

attempt to capture the freer. If a guard (or guards) are present

and are challenged by freer opponents, each guard should pair off

against an opponent in a challenge game (Rock-Paper-Scissors, Odds

& Evens, Tic-Tac-Toe). If the Freer loses the challenge they

must flee or also be captured. If there are no guards left

standing after the challenges the Prisoner is Free!

Quick Reference Sheets

For organizers to use when designing missions on the fly at events

CONSENT

Is everyone on board with participation? How are

you checking? Is any part of your mission dealing with difficult

or triggering topics? Have you made a disclaimer?

Remember the S.E.A.M.S.

Safe for participants.

Enjoyable for everyone, participants and audience alike.

Accessible to ages 18-99 and all shapes, sizes and abilities.

Memorable leave em’ wanting more, but reward what they’ve done.

Sustainable Run it once? Or Ongoing? Do your best but, don't get

burnt out

Shit Happens Some things (like weather) are out of your control.

Do what you can with what you’re given. Expect Delays and

rescheduling.

Yes …..and Remember “Yes … and” is critical to continuing the

Story. Sometimes it's better to accept what's happened, and move

on from there, rather than correct it. Preserving the momentum and

spirit of an activity, is more important to your Participants and

Audience, than getting every loose-end tied up neatly.

DESIGNING A MISSION

What? What are the Goals of the Mission?

When? When and where does the Mission take place?

How? How do Participants complete the Goals?

Armed or Unarmed? What Options do Participants have?

Props: When it comes to Props “Two is One, One is None”

Networking Involve other Teams, and Groups when possible.

Advertising: Before, during and after the Event

Briefing: Give your Participants something to work

towards. Explain the Rules.

Execution: Follow through with the Goals, and be prepared

for sudden changes.

Debriefing: Summarize what your participants have done and

the consequences/results.

Project Your Voice! Participants who can’t hear or understand

what’s going on will quickly lose interest (and may wander

off). Keep your audience engaged with the plot as it

unfolds. Audience participation is good.

Calling Card: leave a Calling Card whenever you take an Item

or Relic with the “Steal-this-thing-” Symbol on it.

Include: What was taken, Who took it, and Where to find it.

(Example Below)

EVENT

MISSION REPORT SHEET

MISSION NAME:

_______________________________________

(To distinguish this

Mission from similar ones)

ORGANIZERS/LEADS:

_____________________________________________________ (Who is

in charge of running this)

WHAT:

______________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

(A brief Summary of what the Mission entails)

WHEN & WHERE:

_____________________________________________________________

(Dates, Times and Locations)

HOW (Checklist)

PROPS/TOKENS:

___________________________________________________________

(What items are needed to run this Mission)

CAST/SUPPORT:

__________________________________________________________

(Who is helping act in/run/facilitate this Mission)

BRIEFING :

(Notes)_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

(Notes on what you want to include in the Briefing, the

In-Character Summary)

SPECIAL RULES: (Notes)

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

(Notes on any Special

Circumstances, Game Mechanic explanations, etc.

Out-of-Character)

DEBRIEFING :

(Notes)_______________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________

(Notes on what you want to

include in the Debriefing, the In-Character Summary Report)

REWARD :

____________________________________ (rewards for completion

[if any])

This Guide is for Entertainment Purposes only. All links to

Copyrighted Material are protected under Fair Use. The Views and

Opinions expressed in this Guide are those of the Author, and do

not necessarily reflect the Official Policy, or Position of the

Starbase 1 LARP, or Starfleet Command-Mojave Outpost. The Author

is not responsible for any Errors or Omissions, or for the Results

obtained from the use of the information presented in this Guide.

Starport Industries:

Missions in the Starbase 1 LARP.

2022 Starport Industries

This Work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International

License.